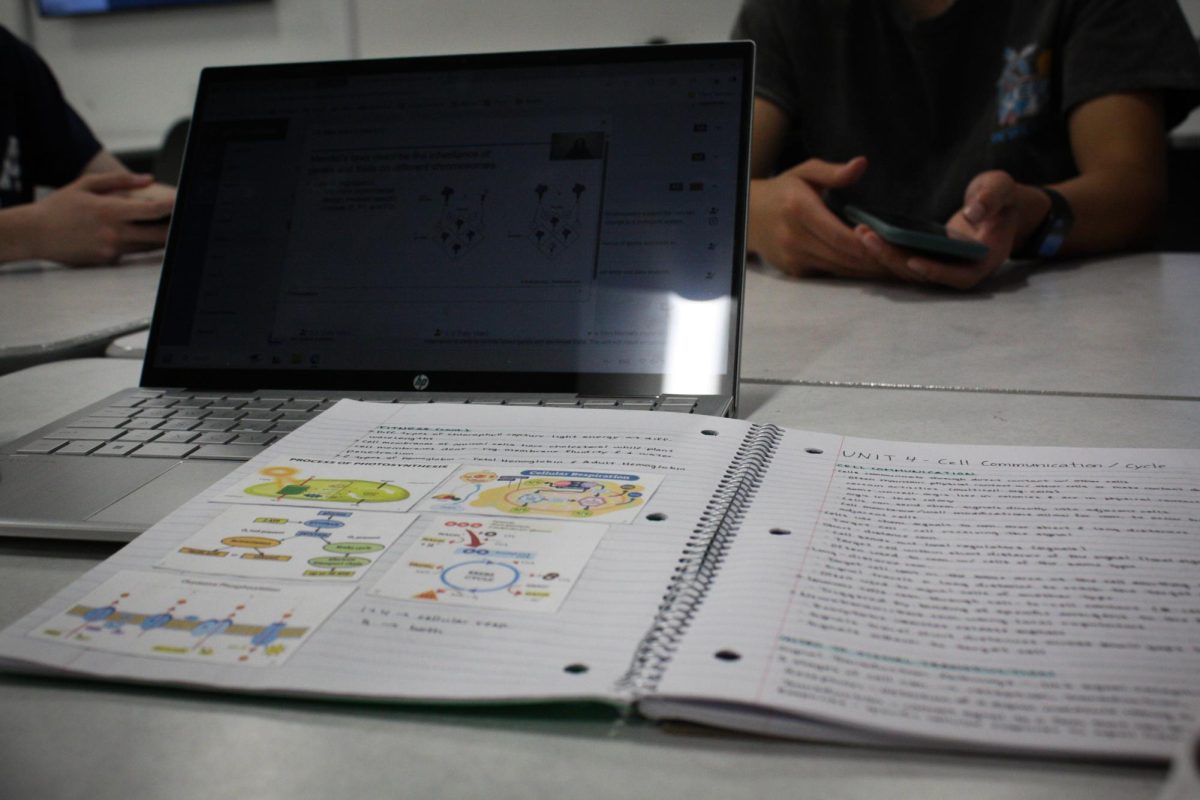

In the back corner of English teacher James Webb’s high school classroom is a collection of large reusable bags. They’re filled with books.

“And there are more that need to be pulled,” he said.

On May 26, 2023, Governor Kim Reynolds signed Senate File 496 into Iowa Law. Along with many other changes, the bill modifies provisions related to school district library programs. Focusing solely on the guidelines affecting Iowa high schools, the new law requires any book depicting a sex act to be removed from school libraries and classrooms.

The bill’s primary aim is to “establish a parent’s or guardian’s right to make decisions affecting the parent’s or guardian’s child.” Multiple aspects of the bill have received backlash from teachers, parents, and students who believe the bill is a dangerous example of the state overreaching. Others view it as a necessary piece of legislation establishing a parent’s right to knowledge and involvement in their child’s education.

The Iowa Department of Education has given no specific list of books that need to be pulled, leaving teachers to determine which books may violate the new, somewhat vague, guidelines. To capture the perspective of educators, I spoke to Ames High English teachers Charles Ripley and James Webb.

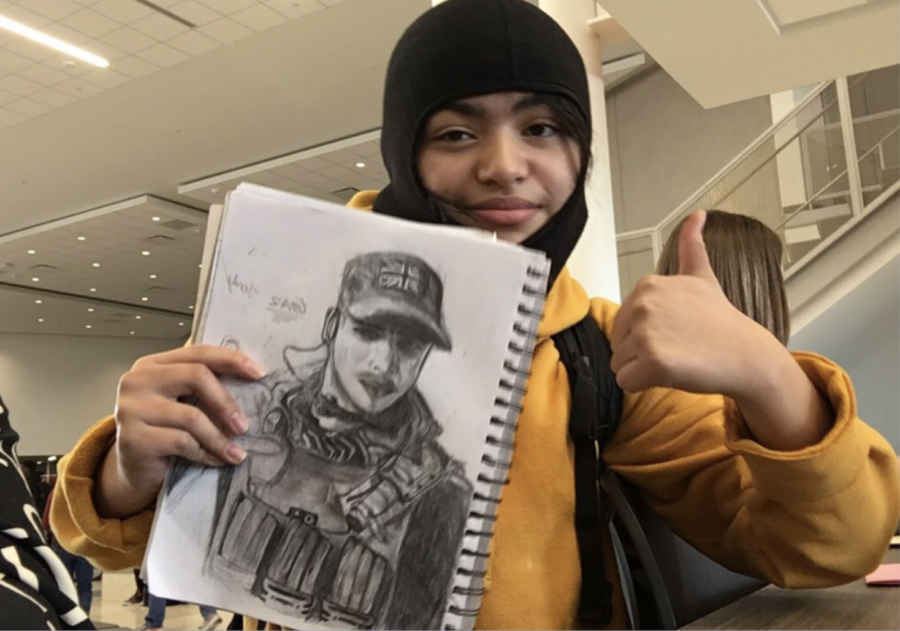

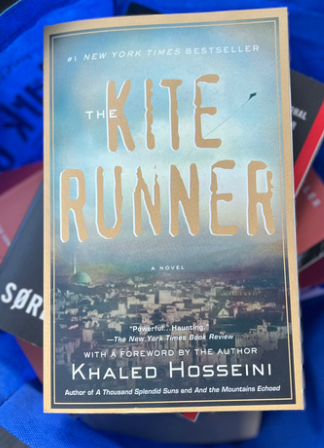

I asked Webb, who’s been teaching for 25 years, about the books in the bags. Some are books one would expect to be removed, such as the suggestive romance books written by Colleen Hoover. Others, he said, were harder to pull: Kite Runner, The Color Purple, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.

(Chantal de Macedo Eulenstein)

Ripley, who’s been teaching English since 2006, is currently reviewing approximately sixty books to potentially be removed from his classroom.

“Beloved by Toni Morrison, A Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. Maybe Slaughterhouse Five by Kurt Vonnegut. Maybe even Brave New World,” he said.

He explained that these books were never forced upon anyone but were simply available for a student to choose. At Ames High, parental objection to reading material has been rare.

Both teachers explain that in such scenarios, teachers have always been willing to offer a student a different book option and work with the parent.

“In my seventeen years of experience, I’ve never heard of a teacher refusing a student another book option or telling a parent no,” Ripley said. “Teachers are always just happy that a student is reading a book.”

“Parents knew upfront what their child was going to read and could choose to opt them out from reading the selected book, and teachers had separate pre-selected texts with assignments ready for those students,” Webb said.

It’s on the teachers to decide how best to determine what books are now either accepted or illegal.

— Charles Ripley

“In the past, we would read a tough book like Invisible Man, which we also can’t teach anymore, but it was a centerpiece in AP Lit,” Webb further explained. “I would send a letter home and say, ‘Hey, we’re going to read this piece of literature. It has some rough edges, and here are some of the things that are in this book that might be objectionable to people. Here’s why we’re reading it anyways and how we tend to deal with those types of situations.’ Parents had control of what their child was reading. And I still had control over what, in my professional opinion, was a really quality piece of literature that would benefit everyone. Parents had rights over their kids, and now parents have their rights over everybody’s kids.”

Now, even students whose parents would have allowed them to read Invisible Man won’t be able to find a copy in the school. Mr. Webb can’t legally hand the book to them, nor can he tell them where else they can find it.

Both teachers are clear that they support parental rights and believe that parents should be involved in their child’s education.

“I think parents should be able to have conversations with their kids about books and topics they don’t feel comfortable about,” Ripley said. “I’m frustrated with the idea that parents or citizens believe they have the right to determine what any student can read, regardless of relation. Some parents clearly matter more than others in regards to this law.”

Ripley continued, “Anytime that, as a society or culture, we decide that certain topics are illegal, or we should be afraid of them, or that they should only be spoken about in hush tones – that’s a pretty dark path to begin walking down.”

According to Webb, the new law is problematic in that it prohibits a sophisticated exploration of challenging topics through literature. The difference, Webb said, is the specifics of that content, its intention, and the manner in which it is discussed and presented.

Graphic internet content is not comparable to stories that highlight experiences lived by many teens, such as Maya Angelou’s The Color Purple, which explores sexual themes, including rape, in a more nuanced way.

“We’re robbing opportunities for students to process these really complex themes and important ideas that do affect people, in a controlled environment, in a safe place,” Webb said.