Proudly, relentlessly wrong

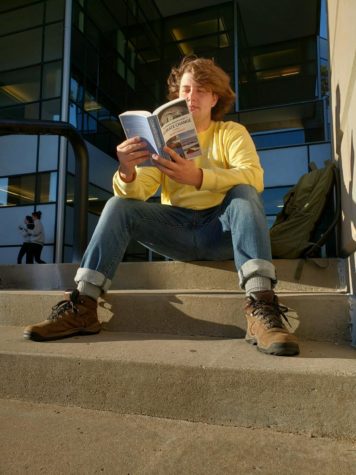

After four years of writing for the WEB, my time to write a senior column is here. It’s my time to write about me. For all my articles up until this point (minus two opinion pieces), I have kept first person out of the piece. I’ve kept myself out of it.

Yes, I have come to every piece with a bias. However, the only way I could insert my opinion was through the voices of others. For instance, for my Josten’s article, my bias as the journalist was towards thinking it utterly stupid to purchase new graduation robes every year, despite many students’ access to perfectly fine hand-me-down robes.

Since I could not simply write my opinion in first person, instead, I started asking students what they thought, as well as interviewing Spence and a representative from Josten’s to understand why the situation is the way it is. Long story short, the journalistic way, no matter how convinced I am of my initial opinion, is to investigate the situation and make sure I am in possession of all the important information before I publish. In this way, my initial opinion is either validated or invalidated by the information I uncover. However, even when I don’t reach a point of reasonable certainty in my opinion about the topic, it doesn’t matter.

As a journalist, my duty is to present multiple sides of a story so, in a way, I wash my hands of having to be the final harbinger of truth. My only responsibility is to present the information accurately.

— Lucas Bleyle

As a journalist, my duty is to present multiple sides of a story so, in a way, I wash my hands of having to be the final harbinger of truth. My only responsibility is to present the information accurately.

Bear with me as I give even more background for the advice I am going to give later in this piece. My AP lit big paper on Crime and Punishment by Dostoyevsky was when I finally articulated this concept. The job of a literary critic is to pull the underlying human truths from the mountains of pages in a novel and lay them bare for all to see. Leaning heavily on the critical analysis of real literary critics, I was able to answer the question: What fundamental truth lies within Crime and Punishment? In its simplest form and removed from the deadweight of plot and story, the truth was this: no individual can achieve objective truth, for truth exists outside of the individual in the culmination of all our perspectives, and the only correct form of an idea is one that is subjected to evolution through dialogue.

I remember the sense of awe I felt coming to that conclusion. For all of you who have ever questioned the worth of the papers you write about classic literature in school, this is why it’s worth doing. Classic novels are often the best recordings of universal meaning, and it’s worth fretting over them until you also have an aha moment as I did from that brick of mid-19th century Russian literature.

I’ve covered a lot of controversial stories these four years on the WEB — stories that had two people who were vehemently opposed to one another. My job as a journalist was to sit down with people from both sides and listen. I was always struck by how reasonable each side sounded, each came from a place of good intentions. As convenient as it would have been, reality is never as simple as a good vs. evil dichotomy. Instead, there is only ever two imperfect sides duking it out for something a little closer to perfect. In this way I believe we do, as a society, approach something that could be called objective truth, but it’s only ever through dialogue. In other words, multiple sides of a story are always more true than any side of a story in isolation.

Which brings me to the only advice I feel I can give with a truly clear conscience: listen to people. Listen to people to the point of absurdity. You will never go wrong by listening to a variety of perspectives. Danger only arises when you close your mind to all but one idea, as Raskolnikov does in Crime and Punishment. And beyond listening to people, accept your own partiality — you will never know everything about everything, but that is okay because you perspective is only part of the bigger truth. Understand that whether what you say is right or wrong, by entering into dialogue you have done something of value. A conversation should be a place where ideas exist without being ideologies — where ideas exist without being identities.

You are never defined by what you said in one moment, because you can listen and learn, and say something more true in the next moment.

— Lucas Bleyle

You are never defined by what you said in one moment, because you can listen and learn, and say something more true in the next moment.

This is the journalistic way. We publish what we think is true. When new information comes in, we update it. It’s a process that is not (or at least should not be) clouded by pride or shame and it’s a model I think we all should follow. So that’s my senior column, it’s not all I have to say, but it’s all I wish to say here. That being said, I am always down to talk.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Ames High School, and Iowa needs student journalists. Your contribution will allow us to cover our annual website hosting costs.

This is Lucas' fourth year on the WEB, and second year as Co-Editor in Chief. He plans to work tiredly to elevate the Web to new heights. He is suggesting...